Christians love conversion testimonies (stories about how people become christian). I am finding I enjoy stories about deconversion: stories about how people start questioning their faith and finally walk away from faith. Christianity, and particularly evangelicalism, is a very strong faith system. It has narrative power, social power, societal power and strong psychological power. You don’t leave Christianity easily — for a lot of people it is a deeply painful and traumatic experience. And the deeper you were in, the harder it is to come out.

I am not sure you can be further in to dogmatic fundamentalist christianity, than to be part of the Westboro Baptist Church. You know, that’s the church that pickets with big signs that God hates gay people, and they go to funerals of dead american soldiers, saying it’s God punishment. They are in the news frequently. I am not including their signs or literal texts, cause they are just too offensive. But you know who I mean.

Well, meet Rachel Phelps. She is part of the family that leads that church, and she used to hold the signs while picketing in different places. Her faith was strong and she was convinced she and the rest of the church were right, and the rest of the world was wrong, and was going to hell.

And then somebody managed to engage her in conversation, on twitter — of all places — and he planted a seed of doubt in her mind. And that started a process that finally led to her renouncing her faith and leaving the church.

Today I listened to a Sam Harris podcast, in which he did an interview with her. You may want to listen to it; it is very impressive.

The question she was asked on Twitter highlighted the logical inconsistencies in her faith. Evangelicalism is not a stupid or simple faith by any stretch of the imagination (regardless of what the European media will tell you), but it suffers from a ton of inconsistencies or difficult questions it can really not answer.

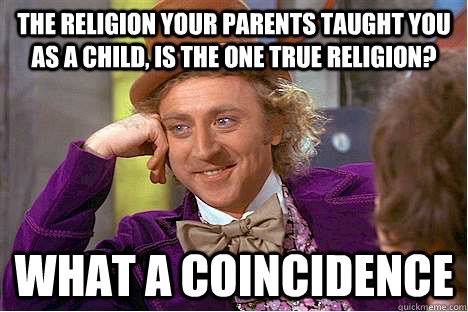

Here is one that Rachel Phelps started to wonder about — and I did also. There are thousands of groups who all believe they have the truth, and all the others are wrong? How do I know, that I (and the group I am with) really DOES have the truth? Or… is it possible, as Rachel started wondering, that we are all just people. With stories, customs, experiences, traditions — and belief systems?

For me this was also a tremendously challenging question. My background was not quite as dogmatic as hers — but it is different only in degree. We did not practice like the Westboro Baptist Church does, but our beliefs were fairly similar. I am shocked by how familiar her experiences sound! But as I was confronted with this question, I started to realise all these groups couldn’t be right. And it was clear they too had scriptures, experiences, traditions that made them absolutely convinced they had the truth — and they were the only ones. The chosen ones! The saved ones! How could I know, for sure, that “we were right”?

Here’s the problem with the evangelical faith: if you start to honestly investigate these questions, you have to, at some point, admit, you cannot substantiate the claim. In the end, we are ‘just people”. The faith is a system, a tradition — one for which the evidence is surprisingly thin.